"Princess Celestia," image retrieved from Pinterest "Princess Celestia," image retrieved from Pinterest I was born this way hey! I was born this way hey! I'm on the right track baby, I was born this way hey! Lady Gaga's throbbing, theatrical voice looped through me, over and over and over again ... for days. And let it be said, the song loop was no worm in my ear. It was more like a unicorn romping her way through me - inside and out - reverberating as truth. That’s the achievement of the song itself says music critic Rob Sheffield: "The more excessive Gaga gets, the more honest she sounds." That unicorn that romped through me was nothing if not excessive. Enough already, I would think, and she would go some more. She insisted on being heard and felt. Every now and then I've actually met a unicorn, and I want to tell you about one whom I had the privilege to know. I will call her Celeste. She recently lost her life to cancer. Celeste was a physician. A pediatrician, in fact. In close proximity to the weeks when she accepted the offer of her first official, non-med student, non-resident, legit, professional job, she was diagnosed with aggressive, life-altering, life-foreshortening cancer. Soon, she reached out to me. We met from the early days of her treatment up to and including the afternoon before she died. I received a text the following day: "Celeste died this morning." Her family welcomed a visit from me later that afternoon. For the first time, I set foot into Celeste's world. In the enclosure of our work together, she and her world were very much in my mind. But it was only hours after she died that this world we'd created took on new life - within the world that had been created long before we ever met. When I visited with her family - her sister, and her parents - it occurred to me to ask about Celeste's birth. Dad told the story something like this: From her earliest days in the womb, we knew she was special. Limbs pushed and poked out in ways both visible and miraculous. A wild shock of hair announced her presence as loudly as and just before her first cries. In her first hours with us on the outside, a well-meaning neo-natologist stopped by to deliver some news: We're looking at ____ here. Your child may not ____. And will most likely ____. It's possible ____. Some of them turn out that way. The message was abrupt, and so was the doctor's departure. He left mom, dad, big sister, and baby to find their own way. With some help, they did. Early on, Celeste knew she was different, and her difference was not something she could hide. As a child, she became an easy target for bullies and an object of glances and glares. Her parents helped as best they could, and it seems, they did a pretty job of it. They supported her through innumerable medical tests, and then later in schools for gifted and talented children and adolescents. In middle school, when Celeste announced she wanted to be a doctor and named the college where she intended to begin her studies, her parents got behind her plan. On a few occasions, when Celeste dyed her hair unicorn colors, they got out of her way. On days they didn’t understand, and maybe didn’t approve, they did the best they could to manage their discomfort and keep supporting their child. When she needed them most, they were there. Celeste bore with them, even when they annoyed or disappointed or frustrated her - and vice-versa. They were always parents and child finding their way. There was also Celeste's sister who had preceeded her in birth. As with most siblings, there were tear-apart events and there were events that bound them together. Once, big sister tried to help younger sister with a bit of a kitchen clean-out. Big sister strenuously advised that Celeste let go of a unicorn mug: It’s atrocious! You really should get rid of this thing! No way! And there was no way, really. How could Celeste part with this massive, bowl-shaped white ceramic vessel? Its red horn poking straight out one side, and its primary-colored rainbow tail swooping around the other to form the handle. The unicorn mug stayed put. Celeste's family found their way into and through and around one another's lives. Celeste found her way in and through and around her family, her friends, her colleagues, her patients and their families. When the end of her life came sooner and more awfully than any of them could have ever imagined, they found their way as best they could in and through and around all of that, too. When I think about the birth narrative her parents shared on the day she died, it seems so poignant to me: how profound beginnings (and endings) can be. A child’s narrative can begin in so many ways ... A child who is "long-yearned for." Or, a child who is not "wanted." A child with a "high IQ." A child who is vulnerable to autoimmune disease. A child with a "dark skin tone." A child whose eyes "look like their father's." Maybe a child who is "healthy and happy," or perhaps one with a "defective gene." And, the child who is a "surprise." And finally, no matter who says what, a child who is beautiful and magic and loved: I was born this way, hey! Apparently unable to avoid the psychadelic Gaga, I went on an expedition to find her "Born this Way" original music video. At over seven minutes long, it is an odyssey in itself; it is complete with its own 2 and a half minute birth-narrative prologue. The prologue is an art piece inside an odyssey inside an expedition ensconsed in pulsating neon color and sound. The pink triangle is notable, at the beginning and the end. I will save the endless observations and references and analyses to the experts. I will say, when I first clicked “play,” I got chills and my eyes welled with tears. The video’s opening image lasts only for a few seconds, but it is undeniably there. It returns for seconds at the end. There is A LOT going on in this video, and this particular image could be easy to miss. I first watched it after my visit with Celeste's family. Lo and behold, for a total of about ten seconds at the beginning and end of the video, a dazzling, sparkly unicorn appears. A dazzling. Sparkly. Unicorn. All I can say is, I believe. With gratitude for Celeste and her family

0 Comments

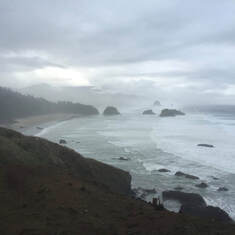

I feel the fragility of our tiny island home these days. It is not the world as I've always known it; or at least, it's not the world I thought I knew. As I contend with my own existential angst, I hold in mind stories of survivors.* They include:

When I'm not working, or watching documentaries or the PBS News Hour, or otherwise engaged, I've decided to watch the show Survivor. I’ve been a fan for years, but now I’m watching every episode from the beginning. At first I thought, why not! More so, I’ve begun wondering, why? The moral and intellectual me even asks really? This is the thing you're doing? I've begun to wonder, why do I find myself uniquely drawn to this show, Survivor, in the midst of this time? The questions continue ... Why do I seem to have shifted from fan to fiendish fan? Why did I begin keeping color-coded spreadsheets on who outwits, outplays, and outlasts season to season? Why do I consult Google Maps at the start of each season and identify the precise geography of each remote location? Why do I do a quick read about the native peoples and histories of these places? Is my guilty conscience on overdrive? Am I unraveling? Do I have a new hobby? Do I need an escape? Am I, in fact, suffering some of the chronic trauma of this time? Deprivation? Overstimulation? Constant upheaval? Uncertainty? All of the above? In a word, Yes. I now possess the Amazon-recommended The Survivor Manual. It’s a manual "based on U.S. Armed Forces survival techniques.” With an Introduction by Survivor Producer Mark Burnett, the manual is stamped with the badge, "Official Book for the Hit CBS Television Show.” When the Manual arrived and I began to look through it, I turned first to the section "On the Move.” … feeling a little stagnant are we? With the flip of a few pages, I went straight to the subsection on "Crossing Quicksand, Bogs, and Quagmires.” Apparently, I did seem to be feeling a little stuck. A little sucked-under. Every now and then I would check my last nerve, and it was frayed. I was restless to move and going nowhere. I let out a guffaw. "If you cannot detour such obstacles,” the Manual advised, “attempt to bridge them by using logs, branches, or foliage." Bridge the angst? I don’t think so. Not this time. If no logs, branches, or foliage are available … If you’ve tried everything you know how to do … If you’ve applied every which kind of way of “coping skills” in your repertoire … If no end is in sight and no help is on the way … The Manual says, “Cross the obstacle.” Shit. The editors of the Manual have seen a quagmire or two or twenty. John Boswell and George Reiger are both former Naval officers and graduates of the U.S. Navy’s SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape) School. These guys say to fall “face downward with your arms spread. Start swimming or pulling your way through, keeping your body horizontal.” When all else fails, they seem to say, do a face-plant into the quicksand. I find an answer. I realize I have planted my face into the thing itself. Survival. I’m doing my best to work with and through it. And maybe, just maybe, I just might move. Perhaps the realm of metaphor is not so opaque. Of course, my Survivor/survivor experience is not equivalent to the experience of any other person who survives. I don’t mean to cheapen the realities of fractured relationships, what if’s, cancer, death, life, violence, and everything happening at once. I’m fortunate to say I’m surviving. I do think it’s useful to take a look at and become curious about the things to which we’re drawn. One of my patients disclosed to me her desire to take all of her pills and “go to sleep” in a ball on her bathroom floor. It’s really not a state of affairs that can always be bridged, or avoided. Instead, there are times we've gone headlong into the depths of depression and the terror of uncertainty. Sometimes she and I move just a bit forward or to the side, or along some indiscernible line; every now and then we go backwards. Lately, she’s been bringing-in stories of women not only surviving but transforming their lives. We laugh. She cries. And we breathe. More and more we’re able to look and to wonder and to think. Space opens up. After analyst D.W. Winnicott, a colleague describes this "potential space." It's a space that can involve "thinking, play, creativity, metaphor, poetry, art, philosophy, and spirituality." It can enlarge the capacity with "which the complex and pardoxical nature of life can best be fathomed." And finally, he says, it is through this space that "surface experience dervies its depth and meaning." Winnicott, also a pediatrician, first articulated this kind of psychologic "space." It is in this space that psychotherapy - and life - becomes quite evocative. I'm thankful for all of the survivors, and I acknowledge the many who have not made it. People whose lives have been ended. And the people whose lives continue to open, including my own. * Patient stories are composite and anonymized.  Richmond fire fighters attend to a vehicle fire on 2nd St. on Sunday, May 31, 2020. Protesters dismissed an 8pm city curfew and marched from Monument Ave. to downtown Richmond. Dean Hoffmeyer/Richmond Times-Dispatch Richmond fire fighters attend to a vehicle fire on 2nd St. on Sunday, May 31, 2020. Protesters dismissed an 8pm city curfew and marched from Monument Ave. to downtown Richmond. Dean Hoffmeyer/Richmond Times-Dispatch "I am are the two most powerful words in the English language." My therapist has made this statement many, many times. (I'm a slow learner - and he is nothing if not persistent!) I hear my own patients say things like, "I am scared." "I am angry." "I am at a loss for words." "I am tired." Or, "I am unable to continue in my marriage." "I am learning a lot about myself during quarantine." Or, "I am a person diagnosed with cancer." Or, "I am gay." "I am White." "I am Black." Each one an assertion of a self, perhaps none so bold as "I am who I am." For me, this idea of I am recalls the story of the burning bush in the Hebrew Bible. The bush "was blazing, yet it was not consumed." Moses became curious and God called to him. In the course of their conversation, God said to Moses, "I am ... I am ..." and finally, "I AM WHO I AM." So profound is this moment between God and Moses, Jews do not use vowels to spell the divine name or say it: YHWH. This name is connected to the Hebrew verb "to be," yielding a translation of "I am." According to some scholars the verb may more accurately be translated, "causes to be," indicating God's action and presence in historical affairs. (Exodus 3:1-15, NRSV) An encounter with I am is one of revelation, disclosure, and intimate contact. One which does not consume, but is beheld. This story suggests God and Moses have that kind of relationship. On the morning of Monday June 1, I awoke to a Facebook feed of things-on-fire. Alarmed by the fires burning in my hometown, the last time Richmond burned I thought, it was the Confederates who scorched the earth - striving to leave nothing behind for the Union army. This time, it was the Museum of the Confederacy and cars that went up in flames. The question, what in the hell is happening (?!), rose up inside me that morning. Shocked, I furiously scrolled through my news feed and saw photos of graphitti-covered monuments. I couldn't believe my eyes. It felt as if the axis of the earth had turned the opposite direction. I felt paralyzed, exhilarated, hopeful, devastated, and astonished. Now I'm reading Ibram X. Kendi's Stamped from the Beginning. I can read 100 pages with crystal clarity. And then, I struggle through the next three, fighting heavy eyelids that want to numb me to history deep in my bones. I've engaged in listening, conversation, and existential sorting. I've measured myself on the antiracist, performative-allyship, racism, and white fragility scales as if to find some non-existent satisfactory grade. And I have confessed. So moved by the words of the Mayor of Richmond in a press conference on Thursday June 4, I felt compelled to write a manifesto. It is a revelation, a disclosure, and a product of deep contact with my Self, my own I am. I've come to believe this kind of encounter occurs in moments either of our own choosing, or in moments that choose us. Moments writ-large, and moments microscopic. For me, Thursday June 4 was all of the above. My Self and I had a serious encounter with each other! In my psychotherapy practice, patients and I become attuned to, observant of, and thoughtful about these moments - as if the moments of encounter, like a burning bush, are not to be consumed, but beheld. In the context of our relationships, I try to help understand and make sense of what's happenning. Even, and especially, in the axis-disrupting moments of life.  So far, I am not in the hospital as a patient or provider. I have no symptoms of COVID, and as far as I know, have not been exposed. I’m hopeful my outcome isn't death but life. Living each day, I find myself keenly aware of how fortunate I am as well as how "prepared" I feel. I confess, I routinely have a large supply of toilet paper on-hand - a relic of my mom's stockpiling, itself a relic of her parents' depression-era habits. But the toilet paper situation is actually not the preparedness I have in mind. Experiences I had as a chaplain have surfaced in my wandering thoughts. For a year at Hopkins, I made daily rounds in the cardiac intensive care units. Within many rooms, I felt awestruck and not infrequently disturbed to see the sophistication and variety of machines - and the fragility of life. Even after 50 or 100 times, I could feel gut-punched again. It was hard. Softness came as I grieved with families. I remember being with a Latinx family in an unusually large, sealed-off room with multiple complex machines doing all of the work otherwise done by a human being's internal systems. The family and I slowly paced around mom who lay in her bed unresponsive, as if we were walking a labyrinth, until the family let go. In general, I'm a person who appears calm. In my years of chaplaincy in hosptials and then in home hospice, a different kind of calm sustained me. Calm made herself available in moments of anguish, heartache, and pain ... moments sublime, surreal, and senseless ... moments of intensity and uncertainty ... moments filled with waiting, rushing, and pressure ... moment after moment for every code called and attended. There was Calm. As a hospice chaplain and as a daughter, I have held hands of fellow human beings as they've exhaled their last breath and shed their last tear. The veil between life and death has seemed exquisitely thin in so many moments I've been privileged to share .... These moments have felt sacramental. NICU nurses used chaplains especially well. One night that felt, itself, like a hazy, waking dream, I was called to be with a mom who had just lost her tiny child. She held her baby in her arms, in her own hospital bed, wheeled-in from her room into the middle of the NICU itself. I felt the love of all the sleeping babies and all the staff who surrounded this duo as I prayed. In a similarly quiet but private moment with parents in a hospital room barely big enough for the three of us, mom and dad asked me to baptize their baby. At first, I didn't understand. Mom was fully pregnant, but she and dad seemed stricken. They tearfully explained their child had died - and they were to deliver him later that day. Laying my hands on mom's belly brought me up close and personal with the finest edges of life and death. For all my "preparedness," whenever my own end occurs, it will be something for which I imagine I will feel unprepared. I'm actually afraid of being alone at the end; and yet, in some ways, each one of us will be alone, even if accompanied. What I've noticed is that we enter and exit life on our own terms and in our own ways. Maybe we feel life's finest edges even now, within ourselves.  Psychoanalyst Marion Milner describes her work as facilitating patients' "growth toward their own shape." I love this idea and it rings true to my own inner work. The shape inside me is something felt. It is not yet realized; it will never be fully realized. It is always emergent. It's about being alive. I think of some of my patients at mid-life, patients whose shapes are shifting both psychologically and physically. One patient marveled as they saw the chambers of their heart beating during a recent ECG. Another patient paused to take-in their own strength and vitality - in the midst of ongoing treatment for metastatic cancer. As they near fifty, both of these patients contemplate questions of mortality, identity, and integrity. To engage what arises from within and without is a kind of surrender - a surrender to the real. Rather than connoting defeat or sumbission, this kind of surrender suggests revolution. The kind of courageous and creative up-ending of what no longer works. In the words of analyst Emmanuel Ghent, this kind of surrender is a "quality of liberation and expansion of self." When I was younger and imagined my own mid-life, I fantasized about wild success in my career. Instead, before I got past my first several years of work, I had undeniable feelings of restlessness and agitation, and unhappiness written on my face. I felt terrified and exposed. A graduate degree, professional credentials, a secure income, and no lack of experience only left me feeling confined. I came to understand that the restriction I felt within my work signaled, in part, walls I'd erected within myself. I've discovered (and discover still), these walls cannot not withstand the foment of self-awakening. Fifteen years later, I now know how it feels to be more fully alive - to live into the shape of myself - and to join with patients as their own shapes emerge. |

AuthorSarah Diehl Archives

March 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed